Naturalism’s problem of Gothic beauty

Gothic architecture, which aims to analogically lead the mind to contemplation of the divine cosmic symphony, seems to resonate strongly with the human spirit – but why?

The great Gothic cathedrals of Chartres, Notre Dame, Milan and so on are exemplary works of architecture and art – I hold that to be self-evident. In fact, I think we can be more sure of Gothic exemplarism than we can be of any theory of aesthetics that seeks to establish some criteria for what makes art good or bad. But what does it mean that Gothic cathedrals seem to appeal strongly to our aesthetic faculties?

To answer this question, we must first understand what Gothic is. You might say: a collection of tall buildings with large stained glass windows, cross-ribbed vaults, pointed arches, and flying buttresses. But that doesn’t quite capture what distinguishes Gothic. Indeed, the old Romanesque cathedrals and abbeys soared higher, at least initially; and Gothic’s main structural features all predate the style, as we shall see. Instead, what distinguishes Gothic is the way its features come together in service of an artistic vision. So what is that artistic vision? And why does it resonate?

It is true that the aforementioned Gothic features – especially rib vaults – serve a structural purpose, redistributing weight to rows of columns or piers, which allows for the construction of thinner walls and much larger windows. But the ribs aren’t purely functional. The columns are often so frail that without the bracing walls between them they couldn’t support themselves, let alone the vault. In addition, the shape of structural members in the Gothic system are often deliberately modified at the expense of functional efficiency, for the sake of a certain visual effect. We see this principle at work in Chartres Cathedral, which employs for the first time piliers cantonnes (compound piers) – four slender colonnettes that surround a powerful central core. The purpose was to eliminate the contrast between the heavy column and the bundle of shafts above that rise to springing of the vault.

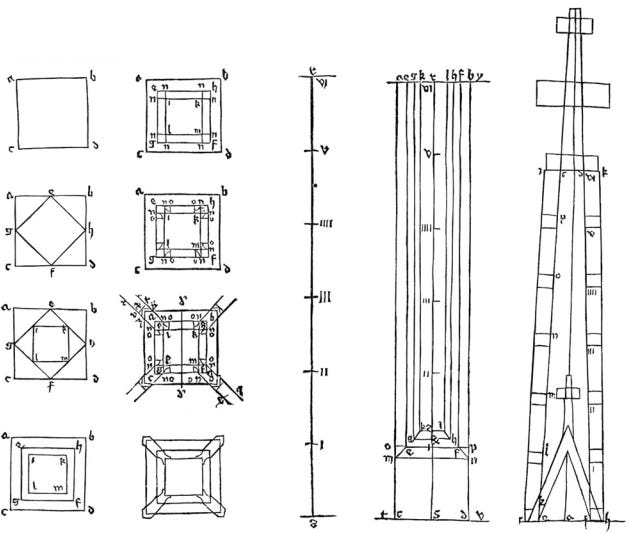

Many have noted that these tall and slender structures suggest upward movement and transcendence. But they also reflect the architects’ fascination with geometric harmony. This is demonstrated by the minutes of a meeting between French, German, and Italian architects in the 14th century, who debated which modular figure should be used for Milan cathedral – they all agreed that it would be built according to a geometrical formula. In fact, the French expert accuses the others of ignoring the dictates of geometry; his opponents deny the accusation, but are happy to concede that they have nothing but contempt for such an architect.

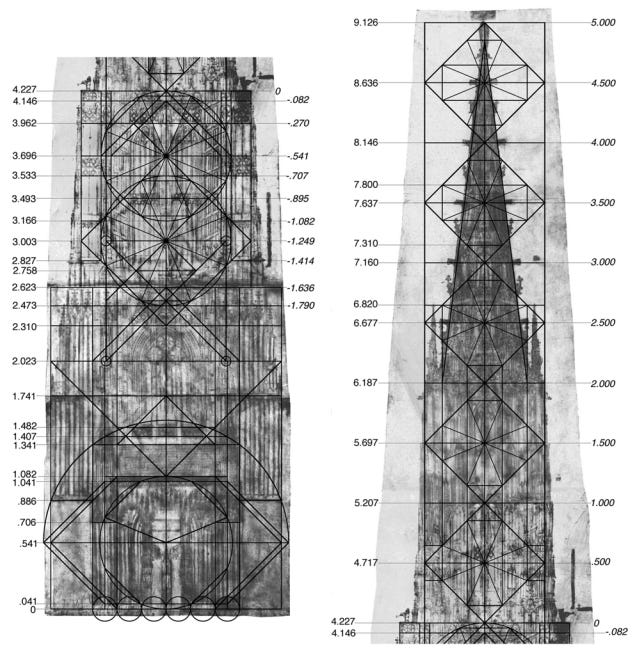

However, the specifics of Gothic design practice has been widely misunderstood since the Renaissance, leading some to question whether geometry was all that important. Indeed, the shockingly non-classical proportions of Gothic buildings famously led Renaissance writers such as Vasari to conclude that this maniera tedesca was inherently wayward and disorderly. But recent surveys using modern computer-aided design systems have shown that Gothic design practice was based on the dynamic unfolding of successive geometrical steps. Gothic buildings often exhibit patterns of self-similarity, in which details such as pinnacles echo the forms of larger elements such as spires, creating a resonance between microcosm and macrocosm – analogous to mathematical fractals.

Why the fascination with geometry? It wasn’t simply that this method of design produced visually pleasing structures, since geometric principles were often applied to areas invisible to observers. For example, all the ribs under the vault of Reims Cathedral circumscribe equilateral triangles – a fact no visitor to the church is likely to notice. Rather, the early Gothic masters, strongly influenced by Augustine and Plato, believed that creation is a cosmic temple designed by a divine architect, who builds using perfect geometrical proportions that account for both the beauty and stability of the cosmic edifice. The early Gothic architects saw themselves as imitating their divine master.

“Thou hast ordered all things in measure and number and weight”

Gothic architecture was the creation of two small groups of men from Île-de-France in the twelfth century, all of whom were mutual friends: Platonists assembled at the school of Chartres and monastic reformers emanating from Citeaux, embodied by Bernard of Clairvaux. Their common bond was Augustinian philosophy.

For Augustine, to truly understand art, one must understand and apply the “scientific” laws that are its essence. These laws are mathematical – and are rooted in neo-Platonic and Pythagorean mysticism. Augustine believed that the ratios that govern music – the number of syllables in a metrical foot, the number of metrical feet within a line, and so on – are in proportion to those in the universe as a whole. This also means that these same principles apply to the visual arts, where the beauty of certain visual proportions derives from their being based on simple – and divine – ratios. Augustine uses architecture as he does music to show that number – as apparent in the simpler geometrical proportions that are based on the "perfect" ratios – is the source of all aesthetic perfection.

Abbot Bernard of Clairvaux – who was largely responsible for Cistercian architecture, which emerged at the same time as Gothic and has several similarities – was strongly influenced by Augustine. Often accused of Puritanism, Bernard believed that churches should avoid superfluous ornamentation so as not to distract from prayer; he denounced the "monstrous" imagery of Romanesque art – and in fact all images besides the crucifixes – and banished them from the Cistercian cloister and church. Yet he remained profoundly musical – believing that music should "radiate" truth, "sounding" the great Christian virtues and kindling the light of truth.

Bernard considered the Bishop of Hippo the greatest theological authority after the Apostles; and he seems to have believed that music and architecture, as “scientific” (in the Augustinian sense) arts, could echo transcendental reality, which painting and sculpture cannot. This is attested to by the legacy of Cistercian architecture, which like Gothic, was based on geometric modules – Augustine's "perfect" ratio 1:2 generally determines the elevation, for example.

The influence of Cistercian upon Gothic architecture is obvious. The two emerged simultaneously, in the same region; and the pointed arch, the sequence of identical, transverse oblong bays, the buttressing arches visible above the roofs of the side aisles, were employed by Cistercian architects before their adoption by the cathedral builders of the Ile-de-France. Then, in the second half of the twelfth century, Cistercian and Gothic ceased to be distinct styles.

Independently of Bernard, Augustine’s influence on the Chartres school is clear – as is shown in the writings of Thierry of Chartres, who was obsessed with the connection between geometry and theology. He even sought to explain the mystery of the Trinity by geometrical demonstration, where the equality of the Three Persons is represented, according to him, by the equilateral triangle, where the square unfolds the relation between Father and Son. The attempt, which appears so strange to us, conveys a glimpse of what geometry meant to the twelfth century.

However, the Chartres school only had access to a fragment of a single treatise of Plato, the Timaeus – poorly translated by Chalcidius and Macrobiu. In the Timaeus, Plato describes the division of the world soul according to the ratios of the Pythagorean tetractys. The aesthetic connotations of this are underscored by Chalcidius who points out that the division is effected according to the ratios of musical harmony. He, as well as Macrobius, insists that the Demiurge, by so dividing the world soul, establishes a cosmic order based on the harmony of musical consonance.

For Augustine, and their followers in Chartres and Citeaux, geometrical and musical harmony serves an anagogical purpose – the ability to lead the mind from the world of appearances to the contemplation of the divine order. This is central to the early Gothic master’s artistic vision. But there is another crucial element to the Gothic vision, which explains the use of large stained glass windows and the creative use of light, which is without precedent or parallel; namely, the mystical theology of illumination.

“God is light, and in him is no darkness at all”

The key influence here was Pseudo-Dionysius (Denis) the Areopagite, a Christian mystic from around the 5th century. However, scholars at that time mistakenly believed his work to be that of the Denis who appears in Acts. This meant his writings, considered to date from Apostolic times, were studied with the respect reserved for the most authoritative expositions of Christian doctrine. But not only was Pseudo Denis misidentified as Denis the Areopagite, he was also misidentified as the Apostle of France (another Denis), the patron saint of the first Gothic cathedral, The Basilica of Saint-Denis. It is quite possible Gothic architecture would not exist if it weren’t for this double misidentification, which led to Pseudo-Areopagite's ascendancy over the entire intellectual culture of medieval France.

The universe of the pseudo-Dionysian writings is a hierarchy of more or less imperfect emanations (“theophanies") of God – whom Denis refers to as “the Father of the lights.” There is a formidable distance from the highest, purely intelligible sphere of existence to the lowest, almost purely material one; but for pseudo-Dionysius, even the lowliest of created things partakes of the essence of God, the qualities of truth, goodness and beauty. Each hierarchy acts as a symbol, which is to say have content that when interpreted points beyond itself, causing an anagogic ascent to the next hierarchy. Knowledge is then gained through interpretation of the symbolic hierarchies. Thus The Celestial Hierarchy states:

“We must lift up the immaterial and steady eyes of our minds to that outpouring of Light which is so primal, indeed much more so, and which comes from that source of divinity, I mean the Father. This is the Light which, by way of representative symbols, makes known to us the most blessed hierarchies among the angels. But we need to rise from this outpouring of illumination so as to come to the simple ray of Light itself.”

For Pseudo-Areopagite, the the whole material universe becomes a big "light" composed of countless small lanterns, where every perceptible thing, manmade or natural, becomes a symbol of that which is not perceptible – a stepping stone on the road to Heaven. Augustine sees geometrical and musical harmony as serving an anagogical purpose, but for Pseudo-Areopagite, everything in the entire universe – if properly understood – serves an anagogical purpose. The human mind, abandoning itself to the "harmony and radiance", which is the criterion of terrestrial beauty, finds itself "guided upward" to its transcendent cause: God.

Is light in the Pseudo-Dionysian writings physical or transcendental? It is not clear the mediaeval mind understood the distinction. However, it is clear that light mysticism was important for Suger of Saint-Denis, French abbot, statesman, and historian who rebuilt the great Church of Saint-Denis in what would come to be known as the Gothic style. We know this from his writings about the reform of the Basilica.

As with Bernard and Thierry, geometry was important for Suger; he talks about “the beauty of length and width” and use of “geometrical and arithmetical” concepts of proportionality. Indeed, Suger opens the Booklet by saying: “what seems mutually to conflict by inferiority of origin and contrariety of nature is conjoined by the single, delightful concordance of one superior, well-tempered harmony.” Like his contemporaries, the Platonists of the School of Chartres, he conceives the universe as a symphonic composition. But the main reason Sugar took the pointed arches of Burgundian architecture and the ribbed vaults from Normandy and combined them with the new flying buttresses was to permit the entrance of more light into the church through an increase in windows and a diminution of walls or partitions using fewer and thinner columns. He writes:

“the elegant and praiseworthy extension […] by virtue of which the whole [church] would shine with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of the most luminous windows, pervading the interior beauty.”

Suger believed that by following the “lights” one can be transferred from this inferior world to the superior one in an anagogical manner (“anagogico more”) – a distinctly Pseudo-Dionysian notion. On the doors of his Basilica these words are inscribed:

“All you who seek to honor these doors,

Marvel not at the gold and expense but at the craftsmanship of the work.

The noble work is bright, but, being nobly bright, the work

Should brighten the minds, allowing them to travel through

the lights.

To the true light, where Christ is the true door.

The golden door defines how it is imminent in these things.

The dull mind rises to the truth through material things,

And is resurrected from its former submersion when the

light is seen.”

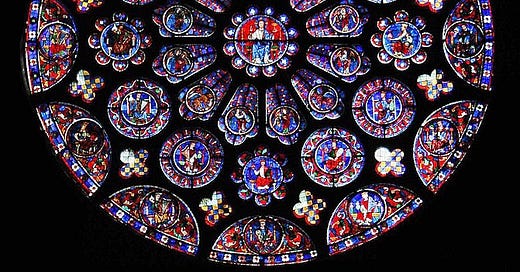

Importantly, light enters Suger’s Basilica through stained glass – which he did not invent but certainly elevated and made more prominent. Suger "vested," as he put it, his “luminous windows” with with sacred symbols. What they meant to him, what they were to mean to others, is best shown in Suger's selection of the scene of Moses appearing veiled before the Israelites. St. Paul had used the image to elucidate the distinction between the "veiled" truth of the Old Testament and the "unveiled" truth of the New. In Suger's interpretation it epitomized his world view, to which, in the footsteps of the Pseudo-Areopagite, the entire cosmos appeared like a veil illuminated by the divine light. The purpose of stained glass was to powerfully impress this upon the mind by transforming the entire sanctuary into a transparent cosmos.

An evidential problem for naturalism

I have sketched an overview of the intellectual milieu of Île-de-France during the twelfth century, which included Bernard of Clairvaux, Thierry of Chartres, and Suger of Saint-Denis – all of whom were friends. These men were, above all, believers in the Augustine notion that architecture can analogically lead the mind to contemplation of the divine order – the cosmic symphony. Bernard and Thierry were focused on geometrical harmony, whereas Suger, more strongly influenced by Pseudo-Areopagite, also focused on illumination. The resulting style, pioneered by Suger, though strongly influenced by Bernard’s “Puritanical” Cistercian monasteries, and later perfected at Chartres, would combine both proportio and claritas and come to be known as Gothic.

At the beginning of this essay, I presupposed Gothic exemplarism. The Gothic sanctuaries of France and elsewhere move the thousands who visit them every year as deeply as do few other works of art. One implication of this understanding of Gothic is, if we want an uplifting built environment, perhaps we ought to adopt geometrical design principles. Although, Suger argued that the mystical vision of harmony can only become the model for the artist if it has first taken possession of his soul and become the ordering principle of all his faculties, which could have something to do with the ugliness of modern architecture… But we still haven’t explained why these buildings, designed specifically to raise the mind to contemplation of the divine, resonate so strongly with the human spirit.

Many have argued that naturalism cannot do justice to the aesthetic dimension of reality, nor explain why the world is so beautiful. But it is especially difficult to understand how, from the perspective of evolutionary psychology, for example, we could have evolved an emotional response to anagogically-aiming representations of geometrical harmony and divine illumination. The evolutionary explanation for the existence of awe – which is connected to our experience of the aesthetic – is that it arises as a combination of fear and wonder to promote ethical concern, prosociality, and generosity. But this doesn’t explain why Gothic architecture, specifically, seems to do this so effectively. Why should something so alien to our hunter-gatherer ancestors trigger our evolved aesthetic instincts?

If theism is true, and human beings are made in the image of God, we might expect our souls to resonate with such a theologically inspired artistic vision. Perhaps the universe is a cosmic symphony – appearing to us a veil illuminated by divine light. Perhaps art can lead our minds from the world of appearances to the contemplation of the divine order. Perhaps there is truth in the Gothic vision.

Kind of related, there is a piece in the latest First Things, quite long, https://www.firstthings.com/article/2023/11/the-men-behind-the-met

It brought me to tears bc of the love between the architect and the craftsmen. I’ll bet something like that was involved in the great cathedrals. How could it not be?

But what then can you say about the giant stadium's which are a feature of the mostly Protestant mega-church's in which thousands of true believers congregate. Giant stadiums which are irredeemingly ugly, and full of raucous noise.